-

Manbhawan-5

Lalitpur, Nepal

-

You may send an email

connect@finedusheel.org

-

Helpline and support

015420252

February 20, 2026

Nepal’s banking system has achieved remarkable growth over the past decade. As of Asoj 2082, total credit outstanding reached NPR 5.67 trillion, serving a population of 29.16 million through A, B, and C class banks and financial institutions (BFIs). Branch networks now exceed 6,500 nationwide, reflecting a significant expansion in physical outreach.

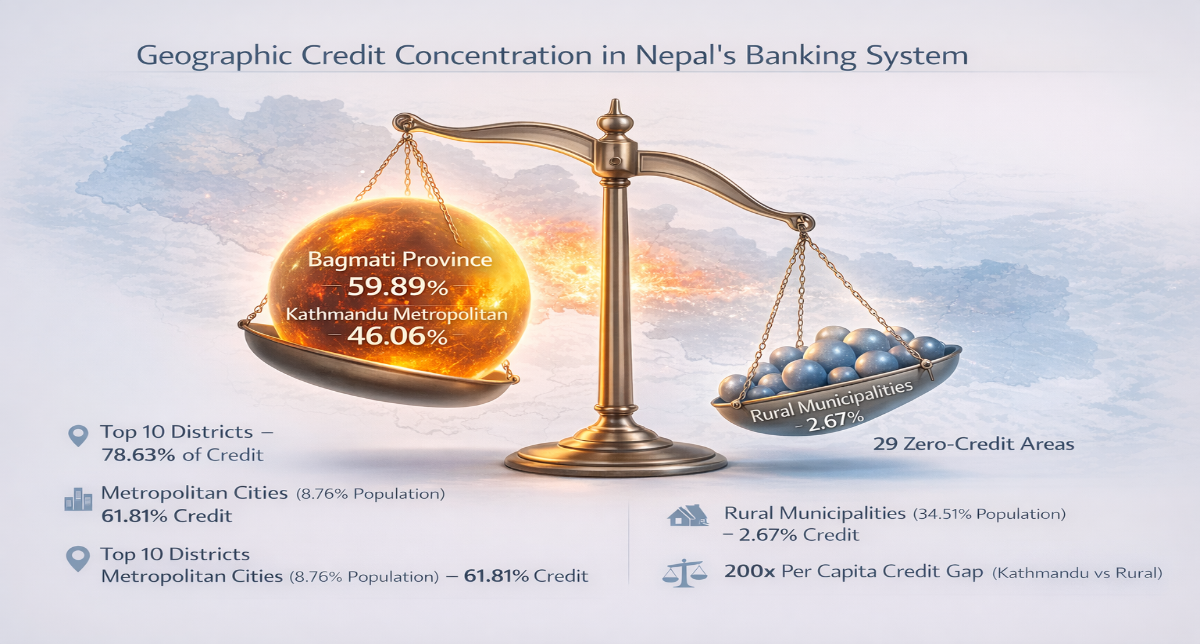

Yet behind this impressive scale lies a structural imbalance: credit remains heavily concentrated geographically, with Kathmandu and Bagmati Province capturing the lion’s share of financial resources. This concentration is not merely a reflection of urban economic activity; it poses systemic risks and threatens the very goals of inclusive financial development.

Credit Concentration: A National Imbalance

Consider the following figures:

- 59.89% of national credit is concentrated in Bagmati Province.

- 46.06% of credit is concentrated in Kathmandu Metropolitan City, which represents only 2.94% of the population.

- Top 10 districts account for 78.63% of total credit.

- Metropolitan cities (8.76% of the population) receive 61.81% of credit, while rural municipalities (34.51% of the population) receive only 2.67%.

- 29 rural municipalities have not received a single formal bank credit facility.

In per capita terms, a resident of Kathmandu has access to over 200 times more credit than a resident in a rural municipality. This is structural financial centralization, not urban strength, and it signals systemic vulnerability.

Provincial Disparities

The provincial credit landscape reveals a sharp imbalance:

Key observations:

- Bagmati receives nearly three times its demographic weight in credit.

- Madhesh receives less than half of what population parity would suggest.

- Karnali’s per capita credit is roughly 15 times lower than Bagmati’s.

- Sudurpaschim and Karnali combined receive just 4.02% of total credit, despite representing 15% of the population.

Such disparities are not only inequitable but also pose macroprudential risks. If Kathmandu faces an economic shock, the concentrated exposure could ripple across the entire banking system.

Municipal-Level Hyper-Concentration

Kathmandu Metropolitan City alone demonstrates extreme centralization:

- Credit Outstanding: NPR 2.61 trillion

- National Credit Share: 46.06%

- Population Share: 2.94%

- Credit per Capita: NPR 3.04 million

- Branches: 801

- Population per Branch: 1,071

The city holds nearly half of Nepal’s formal credit while accounting for less than 3% of the population, yielding a credit-to-population concentration ratio exceeding 15:1.

Urban–Rural Divide

Credit access across local body categories highlights structural exclusion:

Critical findings:

- Metro residents access approximately 91 times more credit per capita than rural residents.

- 29 rural municipalities remain completely unbanked.

- Branch expansion has not translated into proportional credit diffusion, leaving structural exclusion pockets.

Infrastructure vs. Credit Allocation

Despite 6,526 branches nationwide, provinces with significant networks remain underfinanced. Credit approval and booking continue to be centralized, and corporate headquarters clustering inflates Kathmandu-based exposure. While branch expansion supports deposit mobilization and transaction services, it has not produced equitable credit distribution.

Systemic and Macroeconomic Risks

- Geographic Concentration Risk: Nearly half of Nepal’s credit resides in one metropolitan area, making systemic shocks more likely.

- Sectoral Overlap Risk: Urban-heavy lending portfolios concentrate exposure in real estate, construction, and trade finance.

- Federal Imbalance: Political decentralization has not been matched by financial decentralization.

- Migration & Urban Pressure: Credit concentration pulls labor to urban cores, reinforcing spatial inequality.

- Underinvestment in Peripheral Provinces: Areas like Karnali and Sudurpaschim remain consumption-driven and remittance-dependent rather than production-led.

Structural Drivers

- Collateral-heavy lending models favor urban land markets.

- Centralized credit sanction authority in Kathmandu.

- Corporate loan booking at headquarters level.

- Limited credit guarantee penetration in peripheral provinces.

- Risk-weight frameworks that ignore geographic diversification benefits.

- Informal documentation barriers in rural economies.

Policy Reform Options

The goal is balanced risk diversification, not forced redistribution.

- Mandatory Geographic Credit Disclosure: Quarterly reporting by BFIs at province, district, and local levels to improve transparency.

- Geographic Concentration Monitoring: Integrate province-level exposure ratios into macroprudential supervision.

- Incentive-Based Capital Adjustments: Capital relief for productive lending in underfinanced provinces (Karnali, Sudurpaschim, Madhesh) encourages voluntary regional diversification.

- Targeted Credit Guarantee Expansion: Mitigate perceived risk for MSMEs and agricultural value chains in peripheral regions.

- Delegated Provincial Credit Authority: Increase approval limits at provincial offices to reduce Kathmandu-centric bottlenecks.

- Zero-Credit Municipality Activation: Special interventions for 29 unbanked municipalities through cluster-based financing, digital scoring pilots, co-lending structures, and agricultural value-chain financing.

Strategic Considerations for Regulators

A geographically diversified credit portfolio strengthens:

- Financial system resilience

- Regional productivity

- Domestic industrialization

- Federal economic coherence

Credit concentration is not just a developmental issue—it is macroprudential exposure. Nepal can achieve scale in banking, but without structural balance, inclusive financial development remains unattainable.

Nepal’s banking sector has expanded impressively, but growth without balance is unsustainable. Allocating 61.81% of credit to just 8.76% of the population is a structural imbalance that risks economic stagnation outside the capital.

The solution is clear: risk diversification, opportunity equalization, and financial federalism. Political federalism alone cannot succeed without its financial counterpart.

Nepal stands at an economic crossroads. To graduate from least-developed status, boost domestic production, and reduce reliance on remittances, the entire country must access formal credit—not just Kathmandu. A banking system that finances only its capital neglects the nation.

The data is unmistakable. The imbalance is measurable. The conversation is overdue. Inclusive growth demands that financial decentralization follow political federalism. Otherwise, aggregate credit growth will remain a hollow victory, flowing only to a few while the rest of Nepal is left behind.